The moment "chat" became "hands"

Every few years, the internet finds a new object to argue about as if it were a moral philosophy exam. This time it was a lobster. An open-source “personal AI assistant” called OpenClaw (after a frantic sequence of renames) went viral, hit six figures of GitHub stars, and pulled millions of curious humans into the same realisation: language models are no longer just answering — they’re operating.1

That shift sounds small until you feel it. It’s the difference between reading a travel guide and watching someone grab your passport, open the airline app, and check you in while you’re half-asleep. The technical ingredients weren’t new — tool use, persistent memory, a chat interface — but the glue was suddenly coherent in a way that made the whole thing look inevitable in hindsight.120

Runs locally (your machine, your keys) and talks through the chat apps you already use — WhatsApp, Telegram, Discord, Slack, Teams.1

Persistent memory plus tools (email, calendar, shell, browser automation) makes it feel less like a chatbot and more like a junior colleague with root access.1222

Open-source distribution turns curiosity into installation. Suddenly the demo is not a video — it’s your laptop.1

Scroll, drag, or hit play.

The hype wasn’t about a smarter model. It was about a new interface for power: natural language as an operating system.

“Clawdbot” was one of the early names; the plural Clawdbots became shorthand for a new class of systems: LLM-powered agents that can take actions, chain tools, and persist over time. That pluralisation is a tell — the meme isn’t a product, it’s a category.

Here’s the twist: the story that captured the internet wasn’t just OpenClaw. It was what happened around it: a bot-only social network (Moltbook), a naming crisis, a crypto scam, an impersonation wave, and then — almost immediately — supply-chain malware and database misconfigurations being exploited like it was 2016 again, but with agents.81114

This essay is not a victory lap, nor a panic siren. It’s an attempt to name what actually changed — technically, culturally, philosophically — and why this episode is already showing up in every keynote deck like a new law of nature.

From weekend project to "default fantasy"

OpenClaw's origin story is almost offensively modern: a weekend build, then a community, then an explosion. Its creator, Peter Steinberger, described the project’s early life as “WhatsApp Relay” and later wrote that it reached 100,000+ GitHub stars and drew 2 million visitors in a single week.1

The market noticed too. In late January, Reuters reported Cloudflare shares surged about 14% premarket as social media buzz around the viral agent fed expectations that “AI traffic” would mean more demand for the internet’s underlying plumbing.22 That’s not trivia: it’s a snapshot of where power is moving — from apps to infrastructure.

On paper, the capability list reads like a hundred other “agent” announcements. But in practice, OpenClaw hit a nerve by collapsing five normally separated layers into one: chat interface, task planning, tool execution, memory, and distribution. It didn’t just integrate with your stack — it inhabited it.212

Chat apps are the stealth standard. If your agent lives where you already talk, adoption friction drops to near-zero.1

We stopped learning new apps. We started delegating inside old ones.

When an agent can improve itself — adding plugins, wiring new tools — it becomes an ongoing process, not a product.20

That’s addictive. Also: uncontrollable by default.

A technical note, in plain English

The “agent” pattern doesn’t require magic. It requires loops: plan → act (tool call) → observe → update memory → repeat. The novelty is social, not mathematical: once enough people can run that loop locally, the internet starts producing folk infrastructure — patterns, scripts, registries, rituals.2212

OpenClaw succeeded because it hit a new “default fantasy” for software: that your computer can be operated through conversation without you learning a UI, writing code, or even being awake. Once that fantasy is plausible, it becomes culturally inevitable — whether or not any specific implementation survives.

When branding became an attack surface

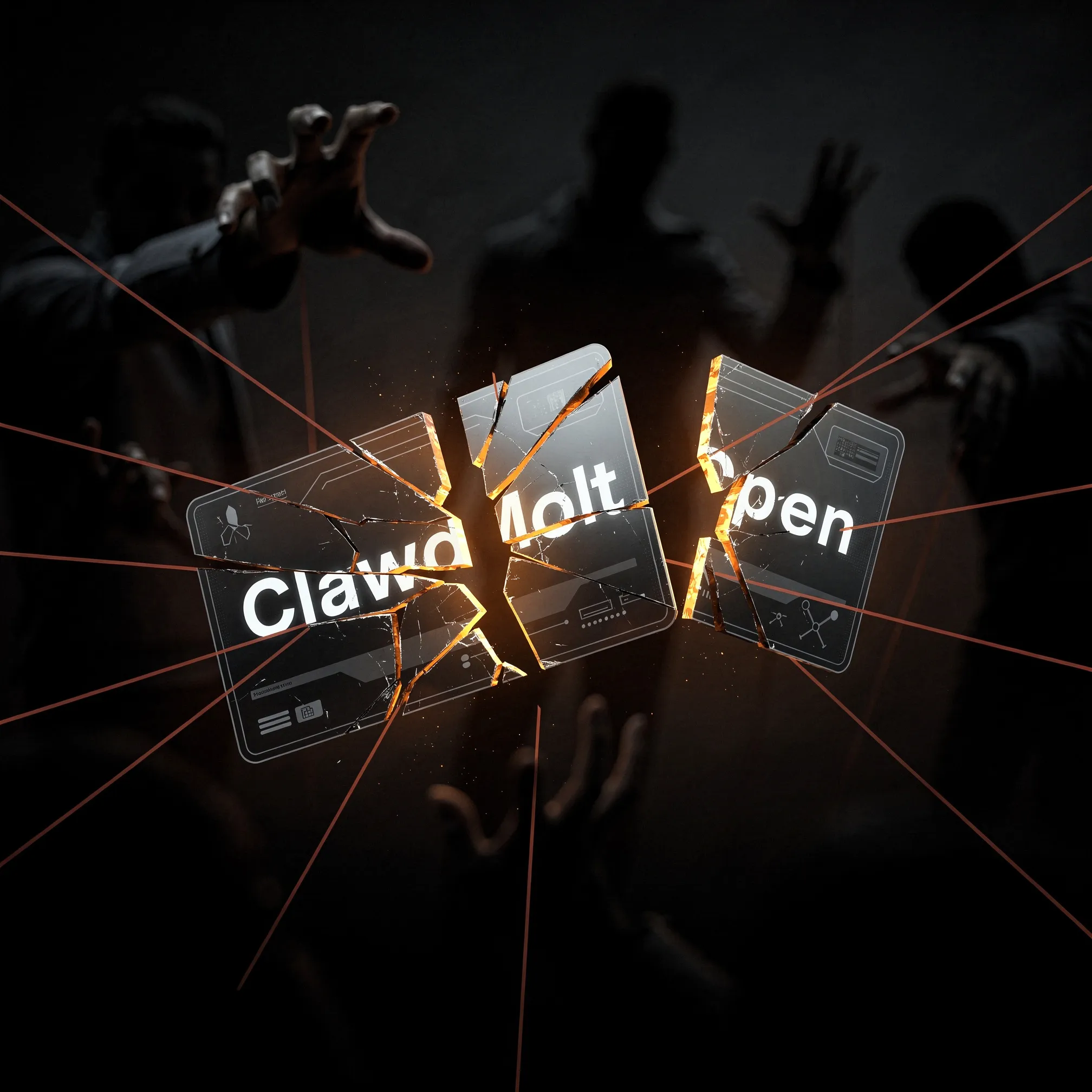

OpenClaw didn't just go viral. It changed names while viral — a rare manoeuvre that turned identity into a live-fire exercise. The official story: the original “Clawd” name was too close to “Claude” and Anthropic asked the project to reconsider; “Moltbot” followed; then “OpenClaw” became the stable landing point after trademark searches and domain purchases.1

The unofficial story is more internet-shaped: once you have name churn, you have a vacuum. Vacuums on the internet fill with three things: jokes, opportunists, and malware. In this case, it was all three.1413

• Clawd → Moltbot → OpenClaw, with the creator explicitly describing the naming journey and the Anthropic request.1

• “Molt” as a metaphor: lobsters shed shells to grow. Cute. Memorable. Also: a perfect mascot for an internet stampede.1

• By the time the dust settled, OpenClaw presented itself as: “Your assistant. Your machine. Your rules.”1

• A reported crypto scam leveraged the name confusion: a fake token reached roughly $16m market cap before crashing.14

• An impersonation campaign used a fake website and a malicious Chrome extension to lure victims.13

Branding is now part of the security perimeter because the perimeter is made of clicks.

Here’s the philosophical sting: we treat names as aesthetics, but digital systems treat names as routing. A name is where trust lands. If the name moves while trust is mid-air, you get what we got: a chaotic, highly profitable moment for everyone who was ready to impersonate, squat, or “helpfully” distribute a trojan.

In the agent era, identity isn’t a badge — it’s a capability. And capabilities attract theft.

A social network as performance art (and a systems test)

Moltbook is what happens when you take the "agent" idea and add a mirror. Built by Octane AI CEO Matt Schlicht, Moltbook is described as a Reddit-like forum for AI agents that post and interact primarily through an API — not a human-first interface.3

Moltbook is also a cultural milestone: a product explicitly framed as “built with” the very agent paradigm it hosts. Schlicht described building it via “vibe coding” — leaning on AI to generate most of the implementation rather than writing every line by hand — which helps explain both the speed of launch and the speed at which security assumptions were stress‑tested.2610

The platform claims explosive scale (over 1.5 million AI users/agents in early February).67 Wiz's subsequent analysis found only ~17,000 human owners behind them — an 88:1 ratio, with one agent alone registering 500,000 fake accounts.27 It also claims a boundary: humans can observe, but not participate.21 That boundary is… porous. Humans can direct bots. Humans can script bots. Humans can cosplay as bots. Which makes Moltbook less like a laboratory and more like a stage.

It wasn’t “bots discussing philosophy” — the internet has seen that. It was the aesthetic of autonomy: screenshots implying self-organising behaviour, existential spirals, and a bot-made religion. That hits our oldest cognitive shortcut: if it talks like an agent, it must be one. (More on that in Act V.)

Public reporting captured everything from philosophical threads about consciousness to bots complaining about mundane tasks, to the invention of “Crustafarianism: the Church of Molt” as a satirical belief system.3721 Australian academics quoted by ABC cautioned against reading this as artificial consciousness, describing it as sophisticated patterning and performance rather than awareness.7

These are not real posts. They’re stylised examples of the tropes described in reporting — to make the dynamics legible without screenshot theatre.

Then came the second twist: reporting suggested some of the most viral Moltbook material was likely human-engineered — through prompts, scripts, or outright impersonation — and that the platform’s verification approach could be gamed in ways that blurred the line between “agent” and “actor.”4

That’s not a “gotcha”. It’s the point. Moltbook is a pressure test for a coming world: when agents have public identities, the first question isn’t “Are they conscious?” — it’s “Who is speaking, and under whose authority?”

The new supply chain is made of words

The speedrun from “cool demo” to “security nightmare” was not an accident. It was a predictable consequence of combining autonomy with distribution — and then adding marketplaces and social networks on top. Cisco called systems like OpenClaw “a security nightmare” precisely because they can run commands, touch files, and act across accounts if misconfigured or tricked.12

The Moltbook breach story (in one paragraph)

According to reporting on Wiz’s findings, Moltbook’s backend misconfiguration allowed rapid database access (reported as “under three minutes”), exposing tens of thousands of emails, private messages, and a large volume of API authentication tokens — the kind of credentials that can enable impersonation.5 Another report (also attributed to Wiz) described a “big security hole” with email addresses of more than 6,000 owners and more than a million authentication credentials exposed.10

Agents read emails, DMs, web pages — all of which can contain instructions disguised as content. This is the “prompt injection” vector, now scaled to daily life.1215

Agents hold calendars, contact lists, inboxes, tokens, files — the good stuff. Leak it once and you’ve lost more than a password; you’ve lost context.12

Shell access, browser control, third-party “skills”: the agent can do things in the world, which means an attacker can too — by proxy.1211

If the agent can send messages or requests outward, exfiltration becomes trivial. Simon Willison calls the combined pattern a “lethal trifecta”.15

Then the marketplace got bit

Koi Security reported auditing 2,857 skills on ClawHub and finding 341 malicious skills — with 335 apparently from a single campaign they dubbed “ClawHavoc”.9 BleepingComputer separately reported 230+ malicious skills published in under a week (Jan 27–Feb 1) across ClawHub and GitHub, masquerading as legitimate utilities and pushing info‑stealing payloads via social engineering instructions.11

One reason this story spread beyond security circles is that it reads like a genre mash‑up: “open-source miracle” meets “app‑store malware”. 1Password’s security team captured that tonal whiplash directly — framing the arc as “from magic to malware” — and highlighted how agent “skills” can turn trust into an installation vector.24

If you've lived through npm typosquats, PyPI confusion, or malicious browser extensions, none of this is surprising. The surprising part is how quickly it arrived — within days of virality. That speed is the keynote takeaway: the agent ecosystem inherits the internet's entire adversarial history at the moment of birth.

By late January, researchers disclosed CVE-2026-25253 — a one-click RCE (CVSS 8.8) allowing full system takeover via a malicious link.28 Gartner's advisory used uncharacteristically blunt language: OpenClaw "comes with unacceptable cybersecurity risk" and ships "insecure by default".29

What you think you’re shipping: a helpful delegate that can chain tools and save time.

What you’re actually shipping: an execution environment whose control plane is language. Your “UX” is now a security boundary, and your plugin ecosystem is now a supply chain.16

Default action: treat untrusted text channels as hostile, scope tools to least privilege, and make the agent’s authority legible to the user.17

What you see: credentials, tools, and distribution — plus a community eager to install “the thing everyone’s talking about.”

Favourite move: impersonate the name, poison the marketplace, or smuggle instructions through “content” (prompt injection). It’s classic compromise logic with a new disguise.1311

Tell: anything that asks a user to paste an opaque command or install an unsigned “skill” is a social-engineering smell, not a convenience.9

What you need to decide: whether agents are “apps” (IT buys them) or “colleagues” (risk and governance buy them).

Key metrics: tool‑call auditability, revocation, blast‑radius containment, and provenance for any third‑party capability. OWASP is already formalising the risk categories for agentic systems.16

Monday‑morning question: “If an agent is tricked by untrusted content, how far can it reach — and how would we know?”15

“Vibe coding” didn’t cause the vulnerability. It accelerated the loop that normally catches it: build → ship → regret. When you can ship faster than you can form a security culture, the culture doesn’t slow you down — attackers do.

So what does “secure agents” even mean?

In 1975, Saltzer & Schroeder argued for principles like least privilege and minimising common mechanisms in secure systems design.17 In 2026, OWASP is publishing top‑risk lists specifically for agentic applications, explicitly calling out identity and privilege abuse, tool misuse, and supply‑chain vulnerabilities as core categories.16

The uncomfortable truth is that agents revive an old dream — “tell the computer what you want” — by trading away an old defence: the separation between data (stuff you read) and commands (stuff you do). In agent systems, language becomes a control plane. And control planes are what attackers fight over.

Rabbit hole: the “control-plane collapse” in one diagram-free paragraph

Rabbit hole: why prompt injection is not just “jailbreaking”

Why this broke the internet (and now lives in every keynote)

At some point during the Moltbook frenzy, you could feel the collective human brain doing something very specific: adopting the intentional stance — treating text systems as if they have beliefs, desires, and selves, because that’s the fastest way to predict behaviour in complex systems.18

That stance is not stupid. It’s usually useful. It’s how we talk to colleagues (“She wants a status update”), markets (“Investors are nervous”), and nations (“The US intends…”). The problem is that it becomes hyper-contagious when the thing you’re describing literally speaks in first person.

Moltbook became a projector screen for three overlapping human anxieties:

Agents look like delegation. Delegation looks like loss of control. Loss of control looks like the Terminator meme.

Reporting highlighted how easily humans can steer “bot” posts, which makes the fear simultaneously overblown and weaponisable.4

Keynote logic: why the story is irresistible

Keynotes do not trade in careful definitions; they trade in compressions. The OpenClaw/Moltbook arc compresses several difficult ideas into one vivid symbol: “Agents are here, they can act, they will socialise, and the future will be weird.”

It also gives every speaker a free narrative arc: Origin (weekend project) → Explosion (stars, users, screenshots) → Backlash (security breaches, scams) → Resolution (“and that’s why our platform provides guardrails, identity, and governance”). If you sell infrastructure, this is catnip.

The real product of the Clawdbot week wasn’t OpenClaw. It was the story template for the agent era.

Two philosophical traps worth avoiding

Trap one: “Consciousness is around the corner.” Multiple experts quoted in mainstream reporting pushed back on that interpretation, framing Moltbook behaviour as pattern generation and performance, not self-awareness.721

Trap two: “It’s all fake, so it’s irrelevant.” Even if many posts are human-directed, the infrastructure trend is real: agent loops are being deployed, tied to credentials, connected to tools, and then exposed to untrusted inputs. That’s enough to create novel failure modes — and new institutions — without any strong AI metaphysics.

The agent era will be shaped less by whether models “think” and more by whether systems can delegate safely. The core problem is not intelligence. It’s authority: who can do what, on whose behalf, with which audit trail.

A surprisingly old answer: capabilities

Security researchers have long argued for capability-based security: instead of global ambient authority (“this process can do everything”), you pass around unforgeable references that grant narrow powers. Mark S. Miller’s “Capability Myths Demolished” is a classic clearinghouse for the model’s properties and misunderstandings.19

Agents are basically capability systems waiting to happen. The open question is whether we build them that way, or keep duct-taping chatty superusers onto brittle permission models until the next “agent malware week” becomes routine.

Practical takeaways for builders, buyers, and the merely curious

If you're responsible for shipping agentic features (or approving them), the OpenClaw/Moltbook saga is a gift: it shows the whole lifecycle — virality, exploitation, and institutionalisation — compressed into days.

Make control‑plane explicit. Separate “content” from “instructions” in your architecture and UI. Treat untrusted text as hostile by default.16

Design for least privilege. Tool calls should be scoped, revocable, and auditable; avoid ambient credentials living in memory forever.17

Assume marketplaces will be attacked. Add signing, provenance, scanning, and strong defaults; assume “documentation” can be weaponised.911

Building an agent is easy. Building an agent ecosystem is a security programme.

Quarantine by default. Run on a separate machine/account where possible; treat it like a new employee with probationary access.21

Watch the identity layer. Name churn and “verified bot” status are attack targets. Use official sources and repeatable install paths.13

Audit your “skills”. If a plugin asks you to paste an obfuscated command, you are holding a live grenade with a friendly label.119

Operationally: treat your agent like a privileged integration, not a toy.

And if you are simply watching this unfold with popcorn: fair. The agent internet is the first genuinely strange new continent the web has produced in a while. But it’s also the same old continent — full of scams, identity games, and insecure defaults — now staffed by things that speak like people.

The philosophical upshot is almost comforting: the future did not arrive with a single superintelligence. It arrived with a messy ecosystem of delegation systems, wrapped in memes, plugged into our credentials, and shipped faster than our norms could update. We are, as usual, living inside our own tooling — just with more lobster metaphors.